In the queer community, there are a lot of stereotypes. Oftentimes I think we conform to these without even realizing. One of these that can be seen in people of all genders, while often focused on the lesbian community is femme and butch gender expressions.

Butch is defined as a person who identifies as masculine, whether physically, mentally, or emotionally. Sometimes it is used as a derogatory term for lesbians, but it can also be claimed as affirmative identity label.

Femme is generally used to describe a person who expresses and/or presents culturally/stereotypically feminine characteristics. This term is also used to describe a specific lesbian identity (i.e. butch/femme). Use the term with caution since in some contexts it can be perceived as offensive.

History

Butch and femme communities were first established in the 1940s and 50s. Butch women “stretched the image of what being female can mean by appropriating signs of masculinity—but without being granted the social and economic power traditionally afforded to masculine males” (Levitt). They still do today. Femme lesbians were “adopting a role of active social rebellion rather than one of weakness or passivity, femme-ininity took on a new form” as they expressed attraction for butch lesbians rather than men. (Levitt)

Stereotypes

- Everyone is either more masculine or more feminine

- If you’re in a queer relationship with someone more masculine, you have to conform to the stereotype of being more feminine, and vice versa

- Similarly, those who present more feminine are only attracted to those more masculine and vice versa

- All gay men are femme, and all lesbians are more butch

- In lesbian relationships, femmes are White, and butches are Black (Walker)

- Femme lesbians can always pass as straight (Walker)

The Gaze

An interesting part about femme women and this idea of them being “straight-passing” is the effect this presentation has on men. As Jean Bobby Noble quotes in the book Masculinities Without Men?: Female Masculinity in Twentieth Century Fictions, (feminine women are) “structurally positioned as an object of both a heterosexual and a homosexual gaze. And while femininity is conferred and consumed in those sexualizing gazes, it is also true that one cannot tell, just by looking, which gaze she will return” (Hemmings). It’s interesting to think about how femme, queer individuals may still have to deal with unwanted attention from men because of their gender presentation.

Gender

I know what you’re thinking. Why do you keep talking about women and lesbians when the binary of butch-femme can extend beyond these identities? I’m glad you asked.

The truth is, butch-femme identities are very stereotyped to the lesbian community. However, this can be seen throughout the queer community. For example, gay men in relationships can also be stereotyped as more masculine or more feminine. This plays with how queer relationships can resemble heterosexual ones, but not always.

Noble gives a good example of butch-femme representation within the trans community when he talks about the film Boys Don’t Cry, about Brandon, who is a transgender man: “This love scene is less an attempt to reassert Brandon as female and more an attempt to construct Lana as femme…Brandon still signifying both masculinity and a kind of vulnerability and woundedness that requires Lana to take care of him both emotionally and sexually…This reconstruction is made possible partly because of the last twenty years of writing that has emerged out of lesbian butch-femme cultures. One of the reasons for the border war between butch and FTM (trans folks) is that, within the twentieth century, lesbianism has been articulated with masculinity vis-à-vis gender inversion” (Noble). This shows that even trans folks deal with this stereotypical gender presentation.

Binary Spectrum

Just as butch-femme relationships can sometimes resemble heterosexual ones, at the same time, it is conforming to a binary of feminine and masculine. I think Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity can be applied here. In her queer theory piece Imitation and Gender Insubordination, she says: “…gender is not a performance that a prior subject elects to do, but gender is performative in the sense that it constitutes as an effect the very subject it appears to express” (Butler). Now theory can be taken in many different ways, but in my opinion, I think this can relate to butch-femme identities. In my opinion, I think femme and butch identities can be performed in that people don’t set out to be either or, but often people fall into one or the other without even really recognizing it.

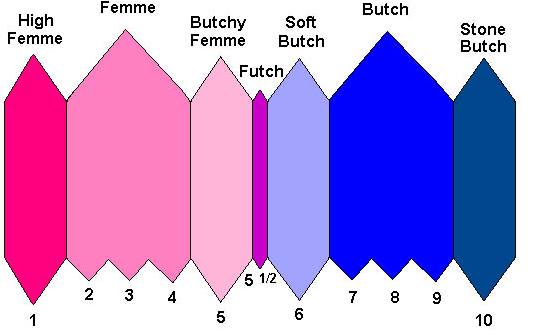

However, just like other gender identities, romantic, and sexual orientations existing on a spectrum, I think butch-femme can be the same. For example, I oftentimes think when people think of femme they think of dresses and skirts. But if you think about it, even casual wear like leggings and tshirts can be on the femme spectrum because it’s not considered to be masculine, and these are binary identities. I think it’s important to remember that you don’t have to conform to either or in a very explicit way and that these identities are personal.

Feminism

It’s always interesting to see how feminists view certain identities, especially within the LGBTQ+ Community, and throughout history. In the 1960s and 70s, butch-femme identities were looked down upon. In the book Butch/Femme: Inside Lesbian Gender, Judith Roof explains lesbian feminism, quoting Charlotte Bunch: “Lesbian feminism is far more than civil rights for queers or lesbian communities and culture. It is a political perspective on a crucial aspect of male supremacy-heterosexism.” In reaction to how people saw butch-femme gender expression, she explained its disappearance: “…in lesbian feminist thought…there was no way to comprehend it as anything other than an imitation of heterosexuality as the form of sex/gender oppression” (Roof). Today, I think we see people embracing butch-femme identities, or at least how others assume their relationship to appear that way.

Sources:

Butler, J. (1993). Imitation and Gender Insubordination. In Henry Abelove et al. (Eds.) The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader. (pp. 307-320). New York, New York: Routlege.

Levitt, H. M., Puckett, J. A., Ippolito, M. R., & Horne, S. G. (2012). Sexual minority women’s gender identity and expression: challenges and supports. Journal Of Lesbian Studies, 16(2), 153-176. doi:10.1080/10894160.2011.605009

Noble, J.B. (2004). Masculinities Without Men?: Female Masculinity in Twentieth Century Fictions. Vancouver, Canada: UBC Press.

Roof, J. (1998). 1970s Lesbian Feminism Meets 1990s Butch-Femme. In Sally R. Munt (Ed.), Butch/Femme: Inside Lesbian Gender. (pp. 27-35). London, United Kingdom: Cassell.

Walker, J. J., Golub, S. A., Bimbi, D. S., & Parsons, J. T. (2012). Butch Bottom–Femme Top? An Exploration of Lesbian Stereotypes. Journal Of Lesbian Studies, 16(1), 90. doi:10.1080/10894160.2011.557646

Obviously, I did not cover everything. Here are some other resources:

“What it’s Like to Toe the Line Between Butch and Femme” by Kayla Layaeon http://www.hercampus.com/life/what-it-s-toe-line-between-butch-femme

“Six Ways That 1950s Butches and Femmes F*cked With Society, Were Badass” by Laura. http://www.autostraddle.com/six-ways-that-1950s-butches-and-femmes-fucked-with-society-were-badass-140167/

“Femme Invisibility: On Passing Right By Your People and Not Being Recognized” by Melissa A. Fabello http://everydayfeminism.com/2014/03/femme-invisibility/