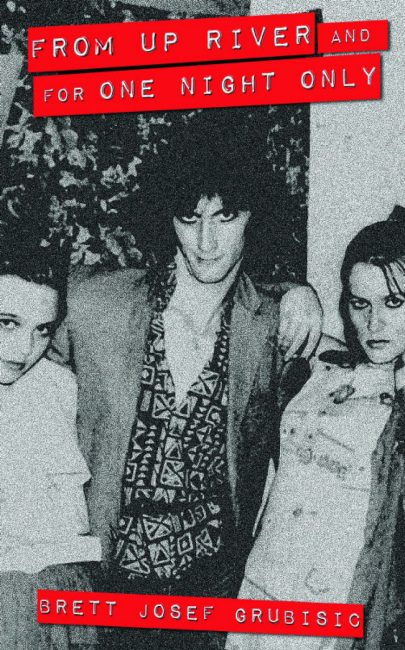

An English Professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Brett Josef Grubisic writes fiction, arts journalism, and scholarship. He’s published three novels: The Age of Cities, This Location of Unknown Possibilities, From Up River and For One Night Only. Other projects include Contra/Diction, Carnal Nation, Understanding Beryl Bainbridge, National Plots, American Hunks, and Blast, Corrupt, Dismantle, Erase: Contemporary North American Dystopian Literature.

I spoke with Brett about teenage dreams, queer loving, and sex work in small-town Canada.

RJB: You have an upcoming novel from Now or Never Publishing, titled From Up River and For One Night Only. Would you pretend I’m an extremely busy and unforgiving agent and give me your best elevator pitch?

RJB: You have an upcoming novel from Now or Never Publishing, titled From Up River and For One Night Only. Would you pretend I’m an extremely busy and unforgiving agent and give me your best elevator pitch?

BJG: OK, here goes: “It’s August 1980 in a Canadian logging town that’s seen better days. Inspired by magazine pictures of London and New York, four students (a pair of gay lads who are friends and their keen younger sisters) decide to form a New Wave band and enter a Battle of the Bands contest. On 13 February 1981, they’re on stage for their first and only performance. During that six-month period before, they’re educated on the compromises, sacrifices, and ethical dilemmas that result from their ambitions.”

RJB: Even though the novel is set in 1980-1981, many of the teenage (mis)adventures are disturbingly familiar to those of myself and my friends in the late 90s—from Jesus camp to queer sex, and even sex work. Do these deviant protagonists reflect the goals and cynicism of ‘Generation X,’ or teens of all decades?

BJG: Life in River Bend City offers these kids what they see as an insulting pittance. Instead of accepting crumbs, they want the whole cake. They seek it, regardless of the lies, secrets, and criminal activities are undertaken to claim it. I’m not so sure it’s a generational thing. Old novels by Edith Wharton and F. Scott Fitzgerald show a similar kind of will-to-power. And there’s Gertrude Slojinski in All About Eve, too. That story was published in the 1940s. For all I know, we could probably trace the archetype back to the ancient Greeks!

RJB: There’s a continual, playful disdain for both wild adolescent dreams and mundane adult realities. At the risk of sounding like an ‘It Gets Better’ video, what would you tell your teenaged self in order to soften the brutal transition into adulthood?

BJG: Despite their naive fantasies about moving to a far-off metropolis and becoming both established and renowned in a matter of months (a belief that, according to televised singing competitions that I see now and then, is more popular now than ever), these kids are savvy enough to understand their native abilities and current circumstances. As gay boys in a small town in 1980, Gordyn and Jay aren’t offered a place at the table. Ditto for Dee and Em, girls who won’t settle for gender norms. They all know they must leave because it’s true. And they all comprehend that as outsiders with unconventional dreams and desires, they need to find that themselves because it’s not going to be offered to them. I think the impulse to ‘get out of Dodge’ and head for the city was the best option at that time.

What awaits them—what awaits all of us—in adulthood in impossible to predict. I’m not convinced there’s much that can be done to soften that, except what they do: cultivate a sense of their individual value and hang on to others who share those outlooks.

RJB: Having read both your 2006 work ‘The Age of Cities’ as well as ‘From Up River’, there’s a strong division between the urban and the rural, which can’t help but lead to other divides: the traditional and the perverse; the mundane and the magical; the heterosexual and the homosexual. This might be a loaded question coming from a polyamorous queer who moved from Wales to central Berlin, but is urban space necessary to sexual and social freedom?

BJG: The easy answer: heterogeneity. By virtue of their size and inherent diverseness, cities tend to be progressive…and filled with anonymous spaces and a beneficial indifference to others’ business. Typically, you can’t and don’t get that in small towns, particularly when sexual minorities are concerned.

Still, there’s something about simply journeying from A to B that’s magical too.

My second novel, This Location of Unknown Possibilities, takes two jaded urbanites to a semi-wild film shoot location in the Okanagan, BC’s arid orchard and grape-growing region. The change of circumstances and exposure to non-urban greenery act as a kind of nurturance that enables beneficial changes to take place.

RJB: The run-down locations and small-town inhabitants of River Bend City are described in detail, with a familiarity which feels like loving contempt, from the run-down Canadian-Asian restaurant to the local head shop and dive bar. How do you feel toward ‘The Bend’?

RJB: The run-down locations and small-town inhabitants of River Bend City are described in detail, with a familiarity which feels like loving contempt, from the run-down Canadian-Asian restaurant to the local head shop and dive bar. How do you feel toward ‘The Bend’?

BJG: Thanks to death, divorce, and other family crises, I moved around a lot when I was a kid. And River Bend City is closely based on Mission, a town where my family set up shop a few times. The novel’s characters are based—loosely—on my deceased sister, my best friend at the time, and his sister; and all of those relationships really developed there, especially during high school. And whenever I think about my formative years, it’s that town that springs to mind. Whenever I visit now, I remain pretty much ambivalent. Your description of “loving contempt” seems pretty accurate. To my eyes at least, there’s not much there. The natural setting is pretty, though. Certainly for queer youths and their supportive, rebellious sisters…there was even less circa 1981. Still, without its pressures, restrictions, and overall strangeness, I wouldn’t be sitting here as I am and writing about it.

RJB: Finally, the 1980s teenagers in the novel yearn for life in the city—New York City. Do you think young Canadians nowadays can dream of Toronto, Vancouver, or Montreal in the same way? Does urban Canada have space for young, fucked-up dreamers?

BJG: As a professor, I read tons of CanLit as a matter of course. Based on that, then, the dominant story of small towns is still “leave or succumb.” From early books by Alice Munro to Margaret Atwood to queer coming of age novels, the predominant trajectory is: leave the restrictive and unwelcoming habitat or suffer the consequences. Offhand, I can’t think of a single novel in which a queer character is depicted as happily settled in a small town context. Yet in queer novels like Don Hannah’s The Wise and Foolish Virgins, Kim Fu’s For Today I Am a Boy, R.M. Vaughan’s Spells, and Tamai Kobayashi’s Prairie Oyster, town culture reflects a conservative heterosexual monopoly that has little to no ‘extra’ space for minorities, sexual or otherwise. In them, characters either die or suffer. It ain’t pretty.

From Up River and For One Night Only is now available from Now or Never Publishing:

http://www.nonpublishing.com/from-up-river-and-for-one-night-only