Ayad Akhtar, Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright of “Disgraced,” has a new drama, “Junk,” directed by Doug Hughes at the Vivan Beaumont at Lincoln Center. Sadly, this new play cannot compare to his previous hit, which tackled race and religion with such incredible nuance. In “Junk,” Akhtar explores the financial world of the 1980s, including an aggressive takeover, insider trading, stock manipulation, million dollar investment portfolios, and of course, controversial junk bonds.

However, after seeing the two and half hour drama, I cannot even confidently say what a junk bond is. This lingering confusion over the financial jargon is the central flaw of the piece: it is inaccessible, almost even incomprehensible to the non-finance majors among us. If we don’t understand what a junk bond is how “debt is an asset”—two of the central principles of the piece—then how are we supposed to understand the details of the plot? For those in the audience who failed economics 101, or prefer to hand over their taxes to an accountant, or who have never once looked up how a specific stock was doing, “Junk” may not be the show for you.

Much like the Oscar-nominated film, “The Big Short,” this play is a good piece of art, albeit one that the majority of audiences will not fully understand. Art that is riddled with complicated (and undefined) terminology can be very isolating to audience members. They get confused, then they get frustrated; soon they give up trying to follow along, and soon they are bored. “Junk” is in danger of setting many of its audience members down this fatal path.

In addition to the litany of fiscal terms, the costume design and plot structure did nothing to help the audience comprehend the piece. The main cast consisted of 11 almost identical white male actors in double-breasted Brooks Brothers-esque suits. The costumes were designed by the usually brilliant Catherine Zuber, but in this production, the casting and the costumes made each character completely indistinguishable. The good guys, the bad guys, the lawyers, the financiers, and the police all blended into the same generically-attractive guy in a suit. Even the actors who played characters around whom the whole plot turned (Steven Pasquale, Matthew Rauch, and Rich Holmes) were often forgettable amid the array of look-alike clones with unmemorable character names and barely distinguished personality traits.

The play had a capricious structure, beginning with a journalist (Teresa Avia Lim) soliloquizing about the growth of greed as a religion in the 80s. However, she did not act as a narrator, protagonist, framing device, or even a major character in this male-dominated piece. Throughout the play, police detectives were recording phone calls to try to get proof of insider trading, but only randomly and in the background. The main character, Merkin (played by Pasquale) had a family drama and a wife he lied to. The CEO of the company he takes over, Thomas Everson Jr. (played by Holmes) had a major psychological plot arc. Among these divergent and often conflicting structures, there was no through-line, no clear plot structure for the audience to follow. Is the show about a ruined journalist? Police take down? A major legal battle? An aggressive takeover? A family business? Who knows.

There is an easy rebuttal to be made against this critique of an indistinguishable cast and a lack of plot: but it worked for “Oslo”! That is correct. “Oslo,” the last major piece in the Beaumont at Lincoln Center, had a similar skeletal form: inspired by true events, mostly male cast who wear almost identical suits, and only one major plot point (in that case, the signing of a treaty, in this case, the sale of a company). While “Oslo” won the Tony Award for Best Play, it seems unlikely that “Junk” will stay on Broadway for very long.

But why? The major difference here is the playwright, although the director and actors can be given some of the credit/blame as well. “Oslo” took a confusing political situation, backdoor deals, and cross-cultural diplomatic relations and made it entertaining, exciting, and even understandable. “Junk” takes a very complicated fiscal takeover and makes no effort to transform it into something comprehensible to a mass audience.

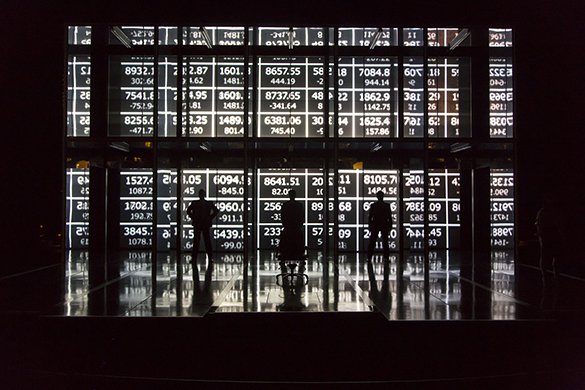

Maybe “Junk” is supposed to teach us a lesson about greed, capitalism, and society’s obsession with wealth. Although the play certainly feels like it is teaching a lesson, it feels more like an economics lecture by an old professor whose powerpoints confuse you and whose voice makes you zone out. Due to “Junk” being so inaccessible, it would be no surprise if the production quickly finds itself struggling to fill the seat in the theater, which would make the show a rare flop for the otherwise impeccable reputation of Lincoln Center. So unless you’ve been doing your homework, reading your econ textbook, and studying those flashcards, maybe skip this lecture.