Although Albee is beloved for many of his plays, there is something extraordinary about “Three Tall Women.” Of course, the semiautobiographical nature is important: much of the play is based on Albee’s own (homophobic) mother. But beyond that — or maybe because of it — the play is tight and fierce and potent. It perfectly blends the emotional vigor of his earlier period (“Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf”) with the experimentalism of his later years (“Seascape”). But the success of a play so small in cast relies entirely on the actresses.

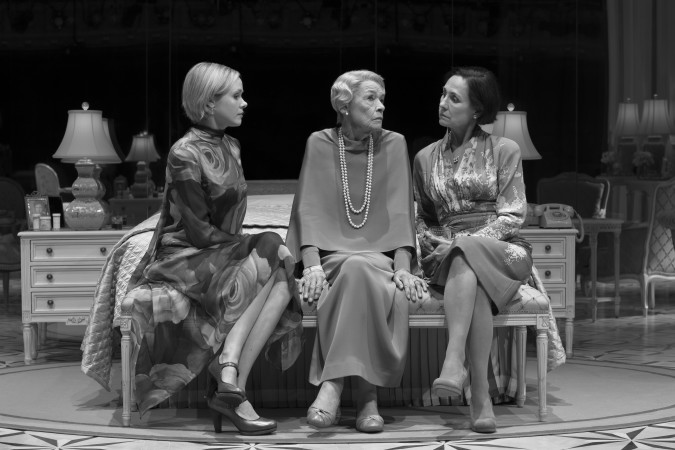

Without a doubt, Glenda Jackson, Laurie Metcalf, and Alison Pill deliver. All three are simply magnificent. Just like the women (or woman) they represent, Jackson, Metcalf, and Pill represent three moments in life, three stages in a career, and most notably here, appeal to three distinct audience groups. The theater-going veterans (I use that term here) flock to see the legendary Glenda Jackson return to the Broadway stage. The middle aged theater aficionados fawn over Laurie Metcalf, the toast of the theater and film scene. The youngins are drawn in by Alison Pill, a name and face they have seen in a litany of film and television performances.

The three actresses play characters named A, B, and C. In the first half of the show that translates to an elderly woman, her middle-aged caretaker, and a young lawyer handling her finances; in the second half they are all the same woman (A) at three different points in her life. Although this sounds confusing, this production merges the transition from the first half’s realism to the second half’s existentialism with ease.

Throughout the entire play, Glenda Jackson is at the helm. Rarely does she let one of the other two women take the wheel, and when she does, it’s only so she can play a joke of them or catch her breath before her next tirade. But far from tyrannical, Jackson’s ferocity is exuberant. Although she begins a senile and forgetful, she is not to be tampered with or touched without permission. Although she is like a stinging snake in the first part of the play, in the second, she is like a wise angel, teaching the other women all the lessons of life they have let to learn.

Though Jackson’s character (A) may be the wise one, it is Laurie Metcalf’s character (B) that thinks she has seen and done it all and knows how the world works. Metcalf transforms from a dowdy nurse to a wealthy adulteress in the span of the play, and does so with the exact mastery we have come to expect from — after all, that’s why we love her. In many ways Metcalf’s middle-aged woman feels the most vulnerable; she may feel like she is at the perfect moment in life, or as she describes it, on top of the mountain with a 360-degree view, she has a lot of unexpected hurt and pain in her future. Of course, Metcalf handles these emotional realization with a quiet severity.

Unlike, Metcalf’s woman (B), Alison Pill’s youthful young professional (C) is aware that she does not know what life holds in store for her. Still tall, still strong, she is confident about what she wants in life and is sure that she does not want to turn into the other women. But fate has other plans for her. Perhaps the weakest of the performers (although this is like calling an Olympic bronze medalist a “loser”), Pill has less emotional depth to handle the roller coaster of lectures on life her character receives in the later portion of the play.

The main design challenge of “Three Tall Women” is the transition from three separate women existing in real time in a real room, to three versions of the same woman in temporal space. This was ingeniously pulled off by the set designer, Miriam Buether, and the costume designer, Ann Roth. In a blink of an eye, the back wall of the beautifully furnished room turned into glass, with an Alice Through the Looking Glass copy of the set on the other side, complete with a mirror wall reflecting the set, the actors, and the audience. This illusion was beautiful and gave the illusion of the three women in an otherworldly space, watching the real world through a glass. The costumes too aided in this transition: in the second half, all three women wore purple, with each in a dress reflecting the period of when the woman was that age.

In the second half of the play, the three women discuss family, sexuality, money, aging, racism, death, and happiness. Each is at a different point in life and provides a unique perspective for each other, most notably the elderly A. Their long conversation is so emotional and educational it leaves you wishing you could go into a mirror world and talk to older versions of your self. But until that can happen, sitting for two hours watching three exceptional actresses perform a remarkable play is a great substitute.